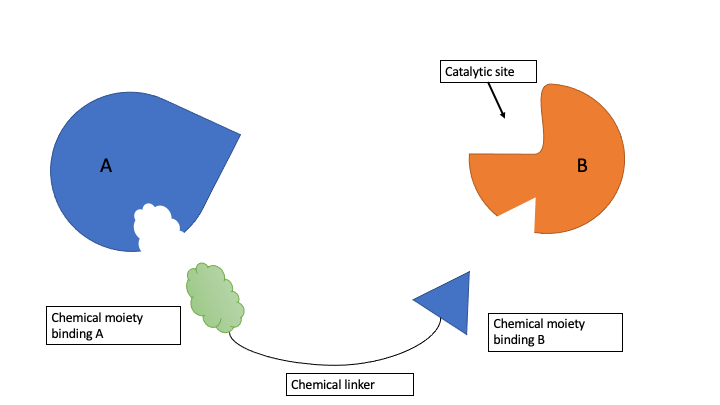

My goal is to find druggable pockets in human enzymes that are non-catalytic. These non-catalytic druggable pockets may then be exploited for proximity pharmacology (ProxPharm), a novel paradigm in drug discovery where chimeric compounds bring two proteins in close proximity to elicit an effect of one protein on the other1. For example, PROTACs simultaneously bind an E3 ligase and a substrate protein, leading to ubiquitination and subsequent degradation of the substrate2. ProxPharm compounds should not inhibit the recruited enzyme (Figure 1). Therefore, a binding location which is not located in the catalytic domain, or is in the catalytic domain but distant from the catalytic site, is favored.

Figure 1. ProxPharm compound binds enzyme (B) and substrate (A) without inhibiting the enzyme.

In our lab, Setayesh Yazdani initiated the Ligandable Genome project based on the project of Jiayan Wang et al.3 Jiayan’s project analysed exclusively human protein structures with bound ligands and assessed the druggability of the corresponding protein domains that were occupied by at least one drug-like ligand in the PDB. Setayesh extended the analysis by mapping cavities in all human proteins in the PDB, whether or not they were bound to small-molecule ligands. She identified the pockets and calculated their properties by using the icmPocketFinder method in ICM (Molsoft, San Diego).

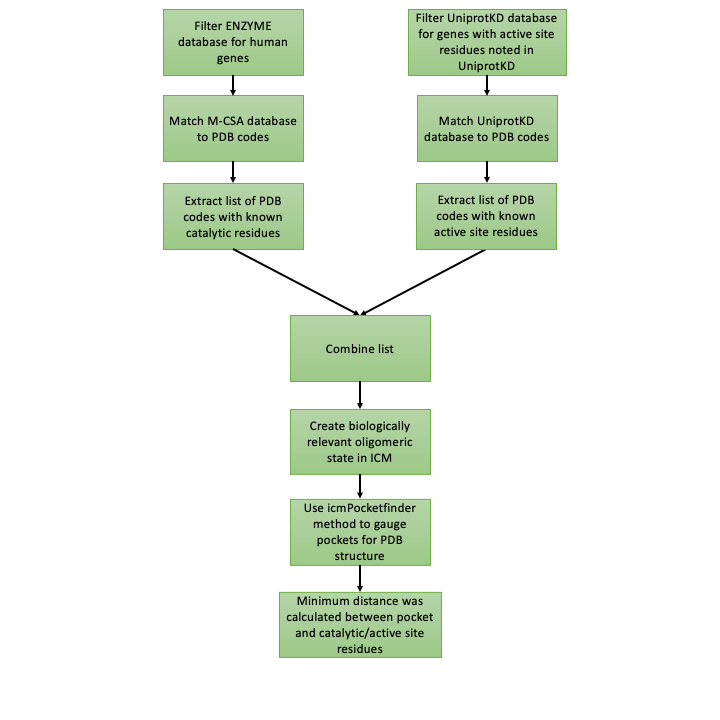

Figure 2. The workflow to distinguish between catalytic and non-catalytic pockets.

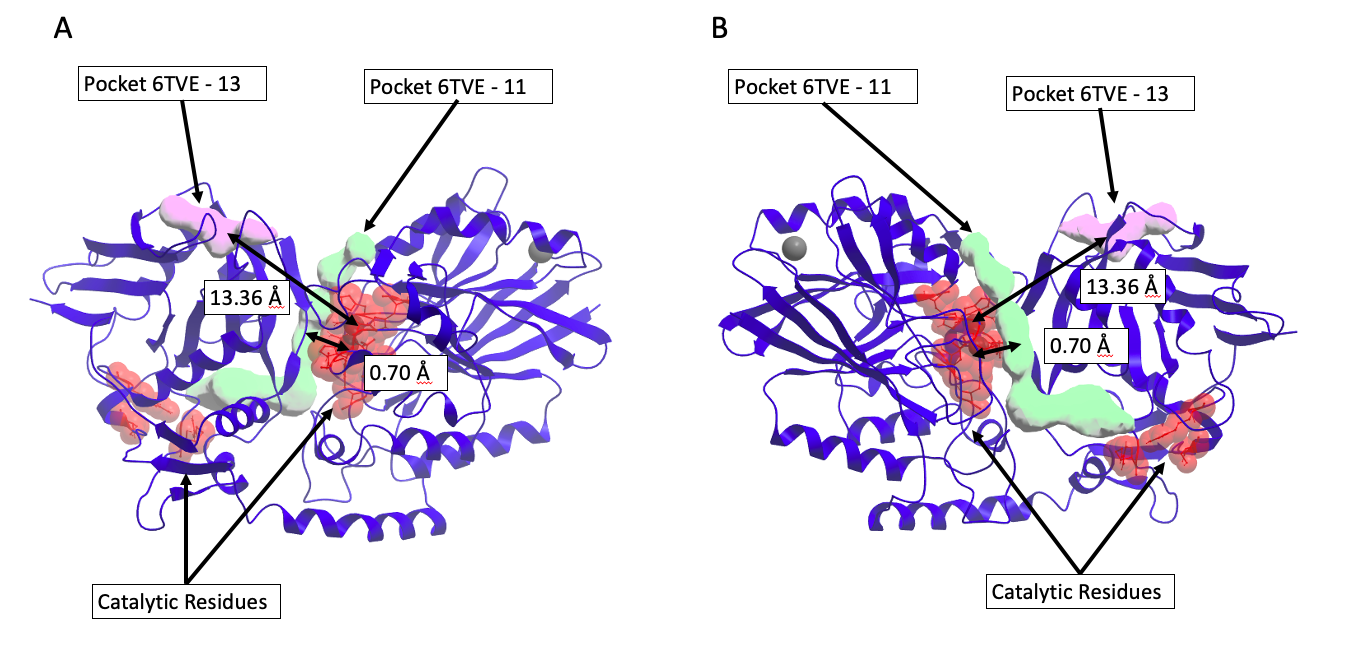

The next important step in this project is to distinguish between catalytic and non-catalytic pockets found by icmPocketfinder in human enzymes. To do this I measure the distance between catalytic/active site residues available from the Mechanism and Catalytic Site Atlas (M-CSA) database4 or available from the UniprotKB database5 and pockets found with IcmPocketFinder (Figure 2). One of the benefits from this approach is that the proximity of the pocket to the catalytic domain is quantified. Figure 3. shows that the minimum distance between the catalytic domain of 5’-nucleotidase (CD73) (PDB code 6TVE6) and pocket 13 is 13 Å.

Figure 3. Discriminating between catalytic and non-catalytic pockets for 5’-nucleotidase (CD73) (PDB code 6TVE)6. Chimeric compounds targeting the purple pocket to recruit the enzyme to a new substrate are far from catalytic residues, and therefore unlikely to inhibit the enzyme. A) Pocket 13 (purple) distance to catalytic residues is 13.36 Å. B) Pocket 11 (green) distance to catalytic residues is 0.70 Å and distinguished as catalytic site.

Using the workflow and the methods listed above, catalytic residues could be assigned to 1487 human enzymes with structures in the PDB, corresponding to 19,510 PDB structures where I identified 140,276 pockets. In my next post, I will analyze which of these pockets are druggable, which are remote from the catalytic site, and will compile a list of enzymes that may be recruited by hetero-bifunctional small molecules to new substrates. If you would like to read the scripts and detailed description of the methods used in this project, please refer to my Zenodo report here.

References:

- Gerry, C. J. & Schreiber, S. L. Unifying principles of bifunctional, proximity-inducing small molecules. Nat. Chem. Biol. 16, 369–378 (2020).

- Nalawansha, D. A. & Crews, C. M. PROTACs: An Emerging Therapeutic Modality in Precision Medicine. Cell Chem. Biol. 27, 998–1014 (2020).

- Wang, J., Yazdani, S., Han, A. & Schapira, M. Structure-based view of the druggable genome. Drug Discov. Today 25, 561–567 (2020).

- Ribeiro, A. J. M. et al. Mechanism and Catalytic Site Atlas (M-CSA): a database of enzyme reaction mechanisms and active sites. Nucleic Acids Res. 46, D618–D623 (2018).

- Consortium, T. U. UniProt: a worldwide hub of protein knowledge. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, D506–D515 (2019).

- Bhattarai, S. et al. 2-Substituted α,β-Methylene-ADP Derivatives: Potent Competitive Ecto-5′-nucleotidase (CD73) Inhibitors with Variable Binding Modes. J. Med. Chem. 63, 2941–2957 (2020).