The familiar, rediscovered.

Biologists interested in the function or the 3D shape of a certain protein face the task of isolating billions of copies of that protein from cells (a process called “protein purification” which does not involve washing or holy water). The aim of protein purification is to start with cells that contain the protein of interest in large amounts and arrive at a sample made of billions of copies of that protein – and not much else. Typically – the pure protein ends up in a plastic tube, in water and perhaps some salt or some pH buffer to make sure that the proteins are happy and stable in the water solution. Protein purification has an illustrious history, and early pioneers such as James B. Sumner, John H. Northrop and Wendell M. Stanley won the Nobel Prize for preparing pure proteins. Once a sample of protein is pure, depending on the questions surrounding it, it can either be used for biochemical assays, or looked at with electromagnetic radiation of some kind, and the results add to the knowledge about the protein, answering questions such as what does the protein do? how does it do it? what 3D shape does it have? how does it move in time? and so on.

Of course – however simple or complex a human endeavour may be – what can go wrong will go wrong – and protein purification is no exception. Proteins are not visible to the naked eye, nor with an optical microscope, and the starting cellular sample contains tens of thousands of different proteins – so every so often biologists set out to isolate protein X – and end up with protein Y (“a contaminant“) in their tube (see for example here). This is an unfortunate outcome: protein purification (like most complex human endeavours) is not for free. At what point is the mistake apparent? Wise biologists set out to check their samples early during the process, and in fact the most important skill for successful protein purification is to be able to track the protein one wants along the potentially long and laborious steps with which it is progressively separated from the initial mix. This way, as soon as it transpires that the protein of interest is lost (this indeed can happen – or perhaps it was not there in the first place?) one goes back to square one without further costly efforts. What is not there (anymore) cannot be isolated.

Serendipity

However, there’s always serendipity. Perhaps protein Y is a novel, interesting one – and its accidental purification will constitute a good result – it may answer a different set of questions. Or perhaps one isolates protein X with another protein Y – and the fact that they stick together reveals that they interact. The proteins that nobody wants to accidentally purify are the ones that we know very well already: ending up with one of those in the pure protein tube is tantamount to discovering that one’s blind date is an old friend. And of course the more abundant and common a protein is – the higher the likelihood that it will be the protein Y that the biologist purifies without wanting to. One such very abundant protein is one of the very first enzymes studied, Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase aka GAPDH. It is so necessary to cells across all animal kingdoms that it is found in large amounts in bacteria, fungi and animals; its stability makes it a very successful contaminant, and one that has been serendipitously isolated in many a study (see for example [1], [2], [3]). The repeated unexpected isolation of GAPDH from protein samples in which biologists did not expect it to be present in the first place has actually revealed that the protein moonlights in multiple roles and very diverse cellular and extracellular environments. Or looking at it from a different angle, a promiscuous protein with a track record for surprise, and one that may well end up turning up on one’s blind date.

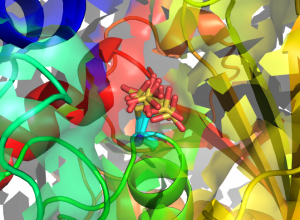

Structures of human GAPDH carrying S-sulfonic acid on the catalytic Cys152. Eight different conformations of the Cys152 S-sulfonic acid (from as many monomers in the asymmetric unit of the crystal) are superposed and represented in sticks (cyan: C atoms; yellow: S atoms; red: O atoms).

We have now joined the group of biologists stumbling on the disappointing discovery of GAPDH in their pure protein tube. In the course of a research effort aimed at the purification of an unrelated enzyme from a fungus, we purified, crystallised and determined crystal structures of human GAPDH. The work has been published in a Wellcome Open Research paper. The protein made it into our sample from the human cells we were using to purify the protein wanted. At the time of this writing, the Protein Data Bank (PDB) contains more than 142 GAPDH entries, eleven of which are of human GAPDH isoforms – so these structures are not exactly a big deal. On the other hand, our crystals turned out to contain GAPDH protein that is chemically modified and bears a Cys-S-sulfonic acid on its catalytic Cystein residue. Although GAPDH Cys-S-sulfonation is known to occur and has already been detected and described, one of these novel human GAPDH crystal structures is the highest resolution human GAPDH structure to date – and the first Cys-S-sulfonated human GAPDH structure to be determined. Sometimes the old friend one ends up in a blind date with is not as familiar as one thought – and may still make for an interesting night out after all.

In 2007 we reported the serendipitous crystal structure determination of lactaldehyde dehydrogenase from from E. coli:

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17173928/

Thank you – the reference has been added to the paper describing the work at https://doi.org/10.12688/wellcomeopenres.15893.1 (preprint at the moment – we are awaiting referee reports).