This is an excerpt from my PhD thesis where I investigated 13 human PR/SET domains from the PRDM protein family and assessed their ability to bind to a fluorinated SAH analog. The research helps to identify which of the PRDMs could be methyltransferases. This work was carried out in the laboratory of Dr. Cheryl Arrowsmith at the University of Toronto and the University Health Network.

Interrogating PR/SET domains for the ability to bind SAH

Authorship attribution:

This chapter contains unpublished work and I am responsible for the overall generation and interpretation of the data included herein with the following mentions: The F-SAH compound was synthesized and kindly provided by Carlos Zepeda, Ontario Institute for Cancer Research (OICR). Shili Duan provided guidance and technical assistance in protein production. Additional proteins were kindly provided by Taraneh Hajian, Elisa Gibson and Dr. Masoud Vedadi from the SGC Toronto. Dr. Scott Houliston advised and supported all NMR experiments, and Drs. Houliston and Cheryl Arrowsmith aided in data analysis and provided guidance throughout the study. This project was prematurely halted due to a catastrophic freezer malfunction during the COVID-19 shutdown.

Introduction

Lysine methyltransferases are a group epigenetic regulators currently being investigated in clinical and pharmaceutical studies for the treatment of certain cancers (Rugo, et al., 2020) (Ilango, et al., 2020) (Hoy, 2020) (Dilworth & Barsyte-Lovejoy, 2019). The majority of all KMT proteins possess a domain with a SET-fold (Schapira, 2011). The PRDM protein family is characterized by the presence of a PRDI-BF1 and RIZ1 (PR/SET) domain, which is a subgroup of the SET domain (FIGURE A1). Currently KMT activity has been reported for some PRDMs (TABLE A1), while some PRDMs are thought to be inactive pseudoenzymes. Since PRDMs are less represented in the academic literature compared to canonical SET proteins (FIGURE A4), it is unclear if these PRDMs are truly pseudoenzyme or if their KMT activity is only yet to be characterized. Distinguishing which PRDMs possess KMT activity would further our understanding of lysine epigenetics and pseudoenzyme-driven biology (Arrowsmith, et al., 2012) (Ribeiro, et al., 2019).

All domains with a SET-fold interact with SAM through a conserved hydrogen bonding network split across two distinct domain regions (Campagna-Slater, et al., 2011). These SAM binding residues in the canonical SET-domains are well conserved, however the corresponding residues in PR/SET domains are less well conserved (FIGURE A2) (H-binding clusters at Regions 1 and 2)]. The only holo-enzyme structure of a PR/SET domains is of mouse PRDM9 bound to a histone H3 peptide and SAH (Wu, et al., 2013). The human and mouse PRDM9 PR/SET domains possess many of the highly conserved SAM-binding residues found in the canonical SET-domains. Lacking any structural evidence, it is unclear if and how many of the PR/SET domains may bind to SAM. Therefore, detecting cofactor binding in PR/SET domains would aid in distinguishing whether certain PRDMs are enzymes or pseudoenzymes.

Here I investigate cofactor binding to understand which PR/SET domains may have the ability to catalyze the KMT reaction. Using 19F-nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy, we measured the binding response for the majority of the human PR/SET domains with a fluorinated analog of the methyltransferase by-product S-adenosylhomocysteine (SAH), 2-fluoro-SAH (F-SAH). 19F-NMR is a sensitive and versatile method to study protein-ligand interactions (Dalvit & Vulpetti, 2019). Using the F-SAH binding response with the PRDM9 PR/SET domain as a positive control for the screening assays, we identified several PR/SET domains that bind F-SAH and therefore likely bind to SAM. Additionally, we detected several PR/SET domains that do not show any evidence of binding to F-SAH, which suggests a lesser affinity for SAM or potentially no affinity. This dataset can be used as a starting point for future discovery of KMT activity in PRDM proteins.

RESULTS

Establishment of the F-SAH binding assay

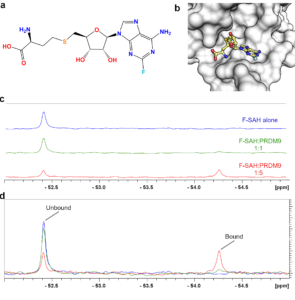

Figure K1. Characterization of F-SAH binding to PRDM9. (a) Chemical structure of 2-fluoro-SAH (F-SAH) and (b) model of F-SAH bound to PRDM9 based on a SAM-bound structure (PDBID: 6nm4). Colour coding corresponds to (a). The effects of F-SAH binding to PRDM9 were measured by 19F-NMR. (c-d) Spectra of 16 µM F-SAH alone and with 1X and 5X molar equivalents of PRDM9 display a concentration dependent decrease in the unbound F-SAH peak and the emergence of a bound F-SAH peak.

We utilized 19F nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy (NMR) spectroscopy to assess whether PR/SET domains may have the ability to bind to the methyltransferase enzyme cofactor. Fluorinated SAH was chosen, rather than fluorinated SAM because SAH and its chemical precursors are more stable across a wide pH range and were therefore more suited to chemical synthesis. The chemical structure of 2-fluoro-SAH (F-SAH) shows that SAH is fluorinated at the 2-position of the adenine ring (FIGURE K1a). Using our structure of the human PRDM9 PR/SET domain bound by SAM, we generated a theoretical model of F-SAH bound to PRDM9 (FIGURE K1b). We observed that the fluorine atom projects toward the solvent and therefore is unlikely to alter the interaction with the protein. Nevertheless, because fluorine’s chemical shift is highly sensitive to any change in its microenvironment, we expected to see perturbation and/or broadening of the 19F resonance when F-SAH binds to a PR/SET domain.

First, we investigated F-SAH alone by measuring a 1D 19F spectrum of F-SAH, which gave rise to a single peak at ~-52.4 ppm. Next, we monitored for F-SAH binding to PRDM9, which is the most extensively characterized methyltransferase among all the PR/SET domain containing proteins (Eram, et al., 2014) (Blazer, et al., 2016) (Allali-Hassani, et al., 2019) (Powers, et al., 2016). We assessed the F-SAH NMR signal alone and in the presence of equal and 5-fold molar equivalents of PRDM9 PR/SET domain, we detected a concentration-dependent decrease in the intensity of the unbound F-SAH 19F resonance (FIGURE K1c-d). Moreover, we observed the emergence of a second 19F signal (~ 1045 Hz up-field at -54.3 ppm) that is from protein-bound F-SAH. As these results were reproducible using two separate PRDM9 protein preparations, we selected 5-fold molar equivalents of PR/SET domain to F-SAH for further experiments.

Screening human PR/SET domains with the F-SAH binding assay

Figure K2. Screening for F-SAH binders among PR domains. (a) 19F-NMR spectra showing 16 µM F-SAH in the presence of 80 µM of the indicated PR/SET domains. (b) Plots of 19F peak integrals for F-SAH in the presence of individual PR/SET domains. All 19F peaks were normalized to the peak integral of F-SAH alone in buffer and the normalized integrals of the Bound and 1-Unbound peaks relative to F-SAH alone were plotted (i.e. F-SAH alone would be located at position [0,0]).

We performed F-SAH binding assays with PR/SET domains from 13 of the 19 human PRDM family members. The PR/SET domains of PRDM 1, 2, 4, 5, 6, 11, 12, 14 and 17 were provided by the SGC Toronto and I purified PRDM 3, 7, 9 and 16. I was able to purify PR/SET protein constructs for PRDM 8, 10, 13 and 15, however these constructs suffered stability issues in our 19F-NMR buffer during dialysis (see Methods) and were therefore not suitable for further study. We collected 19F-NMR spectra for F-SAH with 5-fold molar equivalents of each of the 13 human PR/SET domains (Figure K2a). The relative intensities of the unbound and bound F-SAH peaks varied considerably among the different PR/SET proteins indicating variable binding affinities across the panel of PRDM proteins. To quantify the binding for each PRDM PR/SET domain, we normalized the peak integrals of the unbound and bound peaks for each protein to the unbound peak of F-SAH alone. Specifically, we divided the integral of each peak by the integral of the peak for F-SAH alone. We plotted the normalized integrals of the 1 minus the unbound peak against the bound peak for each PR/SET domain to differentiate each protein’s affinity for F-SAH (Figure K2b). PR/SET datapoints located in the upper, right region of the plot displayed strong binding to F-SAH, while datapoints at the origin indicate no evidence of binding. We used the F-SAH signal in the presence of PRDM9 as an internal control to distinguish a strong binding response. PRDM 4 and 5 were plotted near to PRDM9, indicating a strong evidence response. Additionally, PRDM 14, 12, 7, 11 and 17 exhibited a very strong binding response. We were unable to detect any binding response for F-SAH in the presence of PRDM 3, 1 or 16, using our assay conditions, though we did detected a weak binding response for PRDM 2 and 6. Taken together, this data provides evidence to help prioritize further assays to identify methyltransferase activity among the PRDM family members.

Discussion

Using F-SAH to probe KMT domains

Here we used 19F-NMR to investigate the potential for 13 of the 19 human PR/SET domains to bind a fluorinated analog of the methylation reaction by-product SAH. Using our F-SAH binding assays with PR/SET domains, we identified 7 domains (PRDM 4, 5, 7, 11, 12, 14 and 17) that showed a binding response similar to, or stronger than PRDM9. Of these ‘binding-competent’ domains only PRDM 9 and 7 have reported KMT activity, with accompanying enzyme kinetics data (Eram, et al., 2014) (Blazer, et al., 2016). Interestingly, PRDM7 showed stronger binding to F-SAH compared to PRDM9 (Figure K2). PRDM7 possesses much weaker KMT activity for H3K4me2 substrate peptide compared to PRDM9, with a 100-fold lower rate of catalysis (kcat=1.9×102/h vs 1.9×104/h, for PRDM 7 and 9, respectively) (Blazer, et al., 2016) (Eram, et al., 2014). These catalytic rate differences are mostly attributed to the distinct capacities to facilitate the methyl cation transferase by the catalytic residues (Y357 and S357, in PRDM 9 and 7, respectively). Based on our data, another contributing factor could be that PRDM7 has a stronger affinity for the reaction by-product SAH, which inhibits the catalytic rate. In our F-SAH binding assays, PRDM 2 and 6 showed weak, but detectable, binding compared to PRDM9 (Figure K2). KMT activities towards H3K9 and H4K20 have been reported for PRDM 2 and 6, respectively (Kim, et al., 2003) (Congdon, et al., 2014) (Wu, et al., 2008). This indicates that a weak binding response for F-SAH is associated with known active KMTs. Finally, in all cases where we observed F-SAH binding, we measured a consistent up-field shift (~1040 Hz) in the F-SAH 19F resonance (Figure K2a). This indicates there is a common binding modality with a highly similar microenvironment formed in the bound state across the family.

We also demonstrated the utility of F-SAH as a synthetic chemical probe for methyltransferase proteins. Our approach is comparable to a previous study that reported the binding of the MLL1 SET-domain to a SAM-analog conjugated with a fluorescent tag (Luan, et al., 2016). Comparatively, F-SAH benefits from the smaller size of fluorine, which is positioned on the adenine ring in an orientation that is unlikely to interfere with binding (Figure K2a-b). Additionally, 19F-NMR is capable of detecting low affinity protein-ligand interactions, such as is required for fragment-based screening (Dalvit & Vulpetti, 2019). We surveyed two publicly available databases that quantify protein-ligand interaction data (TABLE K1). We found that SET-fold containing proteins have a range of affinities for SAH with dissociation constants (KD) from low µM to high nM, as well as a similar range for reported half-maximal inhibition (IC50) by SAH. Only RBCMT had affinity data for both SAH and SAM, showing that SAM binds RBCMT with an ~70-fold higher affinity when compared with SAH (Couture, et al., 2006). The authors reported conserved binding modes in crystal structures of RBCMT-SAM and RBCMT-SAH implying that the variations in affinity could not be attributed to the binding conformations, but may rather be attributed to a higher entropic penalty for bound SAH, which possesses additional bond rotational freedom compared to SAM (Couture, et al., 2006). Taken together, we can predict that the upper-limit for the affinity of PRDM9 for F-SAH is less than the known affinity of SAM, which is 18.6 µM (Eram, et al., 2014).

Table K1. Known dissociation constant (KD) and half maximal inhibition values (IC50) of SAM and SAH for SET domain proteins. Binding affinity data available from the BindingDB (www.bindingdb.org) and BindingMOAD (www.bindingmoad.org/) was accessed from the RCSB PDB (www.rcsb.org). Note that BindingDB reports a large range of IC50 values for EZH2.

| Protein | Source | Ligand | KD (µM) | IC50 (µM) | Source |

| EHMT1 | Homo sapiens | SAH | 2.3 | BindingDB | |

| EHMT2 | Homo sapiens | SAH | 0.57 | 2.0 | BindingDB |

| EZH2 | Homo sapiens | SAH | 0.263-16.6 | BindingDB | |

| KMT2A | Homo sapiens | SAH | 2.3 | BindingDB | |

| Kmt5b | Mus musculus | SAM | 11.2 | BindingMOAD | |

| Kmt5c | Mus musculus | SAH | 17.2 | 10 | BindingDB |

| PRDM9 | Homo sapiens | SAM | 18.6 | (Eram, et al., 2014) | |

| RBCMT | Pisum sativum | SAM | 0.29 | BindingMOAD | |

| RBCMT | Pisum sativum | SAH | 21.2 | BindingMOAD | |

| SETD7 | Homo sapiens | SAH | 30 | BindingDB | |

| mSMYD2 | Mus musculus | SAH | 0.18 | BindingDB | |

| SMYD2 | Homo sapiens | SAH | 0.18 | BindingDB |

Interpreting the absence of binding evidence

We identified that PRDM 1, 3, and 16 do not bind to F-SAH in our assay conditions, which is suggestive of the inability to bind to SAM. PRDM1 (initially identified as Blimp-1) is widely understood to lack KMT activity and instead functions as a gene repressor by recruiting specific co-repressors proteins to PRDM1-binding sites throughout the genome (Minnich, et al., 2016). PRDM1 does affect histone methylation, but it does so through interactions with the KMT protein G9a/EHMT2 (Gyory, et al., 2004), the arginine methyltransferase PRMT5 (Ancelin, et al., 2006) and the lysine demethylase LSD1 (Su, et al., 2009). Whether the PR/SET domain of PRDM1 functions as a “reader domain” for specific histone tail modifications is undetermined, however our data suggests that it is unlikely that SAH or SAM would play a role in this ability.

We found that the PR/SET domains of PRDM 3 and 16 do not bind to F-SAH under our assay conditions. However, this does not exclude the possibility that larger or differently generated constructs may possess the ability to bind SAM or SAH. For instance, longer or full-length PRDM 3 and 16 protein constructs were reported to possess KMT activity when purified from either HeLa cells and mouse fibroblasts or SF9 insect cells (Pinheiro, et al., 2012) (Zhou, et al., 2016). Our PRDM 3 and 16 constructs were purified from E. coli and each contained the PR/SET domain along with the first proximal C-terminal zinc-finger motif (ZnF1), which is similar to previous structural and enzyme characterization studies of the PR/SET and ZnF1 of PRDM9 (Eram, et al., 2014) (Wu, et al., 2013). It is unclear if the additional regions outside the PRDM 3 and 16 PR/SET domains and ZnF1 could function to stabilize the cofactor binding site in the PR/SET domain. Interestingly, a previously solved NMR solution structure of PRDM16 demonstrated the absence of internal β-strands that are present in crystal and solution structures of all other PR/SET domains, which could possibly destabilize the cofactor and substrate binding sites (FIGURE A3d). Furthermore, it is unclear if additional factors present in eukaryotic expression systems enable cofactor binding or enzymatic activity.

Future analysis of PRDMs

Future investigation to complete the F-SAH binding screen with the untested members of the PRDM family (PRDM 8, 10, 13, 15, FOG1, and FOG2) would provide valuable data. Additionally, assaying F-SAH binding in competition with (unlabeled) SAM could qualitatively delineate the affinities of the methyltransferase reaction cofactor and by-product, providing further evidence of potential enzymatic function. We detected F-SAH binding in PRDM 4, 5, 11, 12, 14, and 17, and we could not find any studies reporting KMT activity with these proteins. Intriguingly, PRDM 4, 5, 11, 12, and 14 all possess the highly conserved “catalytic tyrosine” (FIGURE A2), which is further evidence supporting KMT activity for these proteins. Importantly, several studies have attributed oncogenic roles for PRDM 4, 12 and 14 in specific cancers (Casamassimi, et al., 2020). Future discovery of enzymatic function in any of these PR/SET domains could provide a novel, actionable target for oncological drug discovery.

Methods

Protein production

PRDM9 (195-385) and PRDM7 (195-392) with an N-terminal 6xHis-tag and TEV protease site were expressed in Escherichia coli BL21 (DE3) codon plus cells from a pET28-MHL vector. PRDM3 (69-235) and PRDM16 (73-256) with an N-terminal 6xHis-tag and TEV protease site were expressed in Escherichia coli BL21 (DE3) codon plus cells from a pET15b/MHL vector. Cell were grown at 37°C in M9 minimal medium in the presence of 50 µg/ml of kanamycin (PRDM 7 and 9) or 100 µg/ml of ampicillin (PRDM 3 and 16) to an OD600 of 0.8 and induced by isopropyl-1-thio-D-galactopyranoside (IPTG), final concentration 0.5 mM and incubated overnight at 15°C. Cells were harvested by centrifugation at 7,000 rpm and cell pellets were stored at -80°C. Cell were lyzed on ice in lysis buffer (20 mM Tris pH 7.5, 300 mM NaCl, 10 mM imidazole, 50 µM ZnSO4, 5 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 0.5 mM TCEP, 0.1% Triton-X 100, 2.5% glycerol, 1mM PMSF, 2 mM benzamidine and Roche complete EDTA-free protease inhibitor cocktail tablet) using a probe sonicator. The crude extract was cleared by ultracentrifugation for 50 min at 50000xg and the supernatant was incubated with TALON Metal Affinity Resin (Takara) at 4oC for 120 minutes with agitation. Resin was washed in wash buffer (lysis buffer with 0.01% Triton-X 100 and lacking protease inhibitors) and bound proteins were eluted using elution buffer (wash buffer with 400 mM imidazole), monitored by Bradford analysis. Protein was dialyzed overnight at 4°C in TEV dialysis buffer (20 mM Tris pH 7.5, 300 mM NaCl, 20µM ZnCL2, 2.5% glycerol, 5 mM β-mercaptoethanol and 0.5 mM TCEP) and incubated with His-tagged TEV protease produced in house at a 1/20 dilution by mass. 0.5 mM CHAPS was added to the TEV dialysis buffer for PRDM 9 and 7, but not PRDM 3 and 16. TEV and uncleaved proteins were removed using TALON resin and soluble protein was loaded onto a Superdex 75 Increase 10/300 GL colum (GE Healthcare), equilibrated with 20 mM Tris-HCl buffer, pH 7.5, and 150 mM NaCl, 2.5% glycerol, 5 mM β-mercaptoethanol and 0.5 mM TCEP at flow rate 0.7 ml/min. Fractions containing PRDM9 protein were pooled and dialyzed into low salt buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.5, 100 mM NaCl, 5% glycerol, 5 mM β-mercaptoethanol and 0.5 mM TCEP). PRDM9 protein was further purified by anion-exchange chromatography on 2 tandemly joined 5 ml HiTrap™ DEAE FF (GE Healthcare) columns along a linear gradient up to 1.0 M NaCl. Purified PRDM9 protein was dialyzed into a final buffer containing 20 mM Tris pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl and 2 mM TCEP. The proteins for PRDM1 (38-223), PRDM2 (2-160), PRDM4 (390-540), PRDM5 (2-226), PRDM6 (194-405), PRDM11 (79-314), PRDM12 (60-229), PRDM14 (212-422), and PRDM17 (1-205) were purified from E. coli expression and kindly provided by Taraneh Hajian, Elisa Gibson and Dr. Masoud Vedadi from the SGC Toronto.

F-SAH binding by 19F NMR

F-SAH was synthesized and kindly provided by Carlos Zepeda, Ontario Institute for Cancer Research (OICR). All PR/SET domain containing proteins were dialyzed overnight at 4oC into 19F-NMR buffer (20 mM Tris pH 7.3, 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM TCEP and 20 µM ZnCl2) also containing 16 µM sodium trifluoroacetate. The concentration of each protein was measured using an absorbance reading at 280 nm and evaluated using their respective theoretical extinction coefficients calculated using ProtParam (Gasteiger, et al., 2005). 100 mM F-SAH in d6-DMSO was diluted to 16 µM F-SAH by adding the dialyzed protein solution to a final protein concentration of 80 µM and then topping off with 19F-NMR buffer to a final volume of 500 µl. For the F-SAH alone sample, only 19F-NMR buffer was added. The solutions were mixed in 1.5 ml polypropylene tubes and then transferred to 5 mm glass NMR tubes.

1D 19F spectra were acquired at 298K on a Bruker Avance III spectrometer operating at 600 MHz and equipped with a QCI cryoprobe with an independent 19F detection coil. Each spectrum was acquired with 3072 scans, an acquisition time of 577 ms, and processed by applying an exponential window function (LB = 20). There was no difference observed in the F-SAH 19F line-shape when signal acquisition was acquired with or without proton decoupling; therefore, all spectra were acquired without proton decoupling. The spectral window was measured from -37.89 ppm to -88.09 ppm and 19F peaks were identified at -75.53 ppm, -52.40 ppm, and -54.21 ppm, for trifluoroacetate, F-SAH unbound, and F-SAH bound, respectively. Processing and analysis were carried out with Topspin 3.5 (Bruker BioSpin). To control for pipetting errors that could result in differences in F-SAH signal intensities, the integral of the trifluoroacetate 19F peak of each PR/SET containing sample was set to equal the integral of the trifluoroacetate 19F peak of the sample with F-SAH alone. To normalize F-SAH peaks, the integral for each F-SAH peak was divided by the integral of the F-SAH peak from the sample with F-SAH alone (i.e. integral of F-SAH alone = 1).

References

Allali-Hassani, A. et al., 2019. Discovery of a chemical probe for PRDM9.. Nat Commun., 10(1), p. 5759.

Ancelin, K. et al., 2006. Blimp1 associates with Prmt5 and directs histone arginine methylation in mouse germ cells.. Nat Cell Biol, 8(6), pp. 623-30.

Arrowsmith, C. et al., 2012. Epigenetic protein families: a new frontier for drug discovery.. Nat Rev Drug Discov, 11(5), pp. 384-400.

Blazer, L. et al., 2016. PR Domain-containing Protein 7 (PRDM7) Is a Histone 3 Lysine 4 Trimethyltransferase.. J Biol Chem, 291(26), pp. 13509-19.

Campagna-Slater, V. et al., 2011. Structural chemistry of the histone methyltransferases cofactor binding site.. J Chem Inf Model, 51(3), pp. 612-23.

Casamassimi, A. et al., 2020. Multifaceted Role of PRDM Proteins in Human Cancer.. Int J Mol Sci., 21(7), p. E2648.

Congdon, L., Sims, J., Tuzon, C. & Rice, J., 2014. The PR-Set7 binding domain of Riz1 is required for the H4K20me1-H3K9me1 trans-tail ‘histone code’ and Riz1 tumor suppressor function.. Nucleic Acids Res, 42(6), pp. 3580-9.

Couture, J. et al., 2006. Catalytic roles for carbon-oxygen hydrogen bonding in SET domain lysine methyltransferases.. J Biol Chem, 281(28), pp. 19280-7.

Dalvit, C. & Vulpetti, A., 2019. Ligand-Based Fluorine NMR Screening: Principles and Applications in Drug Discovery Projects.. J Med Chem, 62(5), pp. 2218-44.

Dilworth, D. & Barsyte-Lovejoy, D., 2019. Targeting protein methylation: from chemical tools to precision medicines.. Cell Mol Life Sci, 76(15), pp. 2967-85.

Eram, M. et al., 2014. Trimethylation of histone H3 lysine 36 by human methyltransferase PRDM9 protein.. J Biol Chem, 289(17), pp. 12177-88.

Gasteiger, E. et al., 2005. Protein Identification and Analysis Tools on the ExPASy Server. In: J. M. Walker, ed. The Proteomics Protocols Handbook. s.l.:Humana Press, pp. 571-607.

Gyory, I. et al., 2004. PRDI-BF1 recruits the histone H3 methyltransferase G9a in transcriptional silencing.. Nat Immunol, 5(3), pp. 299-08.

Hoy, S., 2020. Tazemetostat: First Approval.. Drugs, 80(5), pp. 513-21.

Ilango, S. et al., 2020. Epigenetic alterations in cancer.. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed), 25(1), pp. 1058-109.

Kim, K., Geng, L. & Huang, S., 2003. Inactivation of a histone methyltransferase by mutations in human cancers.. Cancer Res, 63(22), pp. 7619-23.

Luan, Y. et al., 2016. Design of a fluorescent ligand targeting the S-adenosylmethionine binding site of the histone methyltransferase MLL1. Org Biomol Chem, 14(2), pp. 631-8.

Minnich, M. et al., 2016. Multifunctional role of the transcription factor Blimp-1 in coordinating plasma cell differentiation.. Nat Immunol, 17(3), pp. 331-43.

Pinheiro, I. et al., 2012. Prdm3 and Prdm16 are H3K9me1 methyltransferases required for mammalian heterochromatin integrity.. Cell, 150(5), pp. 948-60.

Powers, N. et al., 2016. The Meiotic Recombination Activator PRDM9 Trimethylates Both H3K36 and H3K4 at Recombination Hotspots In Vivo.. PLoS Genet, 12(6), p. e1006146.

Ribeiro, A. et al., 2019. Emerging concepts in pseudoenzyme classification, evolution, and signaling.. Sci Signal, 12(594), p. eaat9797.

Rugo, H. et al., 2020. The Promise for Histone Methyltransferase Inhibitors for Epigenetic Therapy in Clinical Oncology: A Narrative Review.. Adv Ther. , 37(7), pp. 3059-82.

Schapira, M., 2011. Structural Chemistry of Human SET Domain Protein Methyltransferases.. Curr Chem Genomics, 5(S1), pp. 85-94.

Su, S. et al., 2009. Involvement of histone demethylase LSD1 in Blimp-1-mediated gene repression during plasma cell differentiation.. Mol Cell Biol, 29(6), pp. 1421-31.

Wu, H. et al., 2013. Molecular basis for the regulation of the H3K4 methyltransferase activity of PRDM9.. Cell Rep, 5(1), pp. 13-20.

Wu, Y. et al., 2008. PRDM6 is enriched in vascular precursors during development and inhibits endothelial cell proliferation, survival, and differentiation.. J Mol Cell Cardiol, 44(1), pp. 47-58.

Zhou, B. et al., 2016. PRDM16 Suppresses MLL1r Leukemia via Intrinsic Histone Methyltransferase Activity.. Mol Cell, 62(2), pp. 222-36.