Before I get into the details of my project and share my results, I would first like to give a brief background on HTT.

What is HTT?

HTT is a protein that is encoded by HTT, the gene, and it stands for huntingtin. This protein is heavily implicated in Huntington’s disease (HD), a disease that leads to movement, cognitive and psychiatric impairment, similar to Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s. Like these other neurodegenerative diseases, the symptoms of HD are due mostly to the progressive loss of neuronal function and/or structure.

Genetic basis of HD

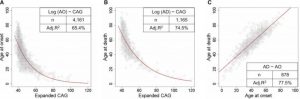

The loss of neuronal function and structure in HD is believed to be due to a mutation in HTT. This mutation occurs in the region of the genetic sequence HTT which contains a repeated CAG sequence, which codes for glutamine (also written as Gln or Q) in the HTT protein. This region is called a polyQ region due to the high number of Q repeats. In HD, mutations in HTT lead to an abnormally large number of Q repeats. Normally, the number of repeats in the polyQ region of HTT is around 35. However, in individuals with HD, the number of repeats are higher, with some up to over a hundred repeats! Studies have shown that the number of repeats correlates with the age at onset and age at death in people with HD, with a higher number of repeats leading to a lower age at onset and age at death.

Figure 1, Keum et al., Am J Hum Genet. 2016 Feb 4; 98(2): 287–298. Published online 2016 Feb 4. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2015.12.018

How does mutant HTT lead to HD?

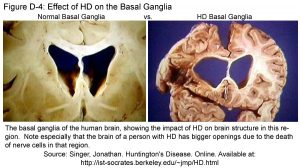

The large number of Q repeats in mutant HTT causes improper folding of the protein and the dysfunction of HTT. This leads to protein aggregation and accumulation in neuronal cells, which may in turn sequester other proteins and prevent them from carrying out their normal function. Ultimately, this leads to cell death. Extensive neuronal cell death causes the symptoms of HD, which include movement, cognitive and psychiatric impairment. Death is often caused by aspiration pneumonia or cardiovascular disease.

Source: http://web.stanford.edu/group/hopes/cgi-bin/hopes_test/the-basic-neurobiology-of-huntingtons-disease-text-and-audio/#what-parts-of-the-brain-are-most-affected-in-hd-patients

Can anyone get HD?

HD is an autosomal dominant genetic disease. This means that the mutant form of HTT (with an expanded polyQ region) passes from parent to child. Moreover, the child only needs to inherit the mutant HTT from one parent to get HD. As such, if either parent has HD, any child of theirs will have a 50% chance of getting HD. However, there are rare cases in which a person gets HD without either of their parents having HD. Some studies have shown that the number of CAG repeats increases over generations, and it is possible that either parent of such individuals has a ‘borderline’ number of repeats that is larger than normal but not enough to cause HD.

How is HD treated?

There is currently no cure for HD, and treatments are solely to manage the symptoms of HD.

As you can see, HD is a devastating disease. It is hoped that this project will increase our understanding of both the normal and mutant forms of HTT and their roles in the biological function of cells.

Very interesting. Good stuff!

Important research you are doing. Huntington patients have fewer cancers than the population. A group studying this found the Huntington gene has has significant cancer-fighting properties leading to questions about treatment for both diseases. My understanding is that cancer involves a multi-step process and I wonder if there any other genes you found that were impacted by Huntington’s. If another gene is elevated, that could be a target too.

Hi Howard, thanks for your comment! Yes, you are right that there are a number of studies that have shown cancer incidence is lower in patients suffering from HD, and this paper published recently by Murmann et al. in EMBO Reports (http://embor.embopress.org/content/early/2018/02/07/embr.201745336) showed some very interesting findings on how the huntingtin trinucleotide repeat might have the potential to be developed into a cancer therapy, which has very exciting implications for both the fields of cancer and HD! It’s a great idea to follow up on other gens that are dysregulated with the onset of HD. This might not only provide us with other targets for potential cancer and HD therapy, but will shed light on the mechanisms involved, especially in the case of cancer, which as you say, is a multistep process. Moreover, different cancers have different aetiologies, and therefore therapies are becoming more targeted and personalised. There are some known dysregulated genes in HD, such as dopamine receptors, huntingtin interacting proteins and even transport proteins, and they are definitely worth looking at for both cancer and HD.